Richiepiep

Administrator

From: DGA Monthly (DGA = Directors Guild of America)

http://www.dga.org/news/v25_3/feat_todd.php3

Todd Holland

Keeping Malcolm in the Middle:

By Darrell L. Hope

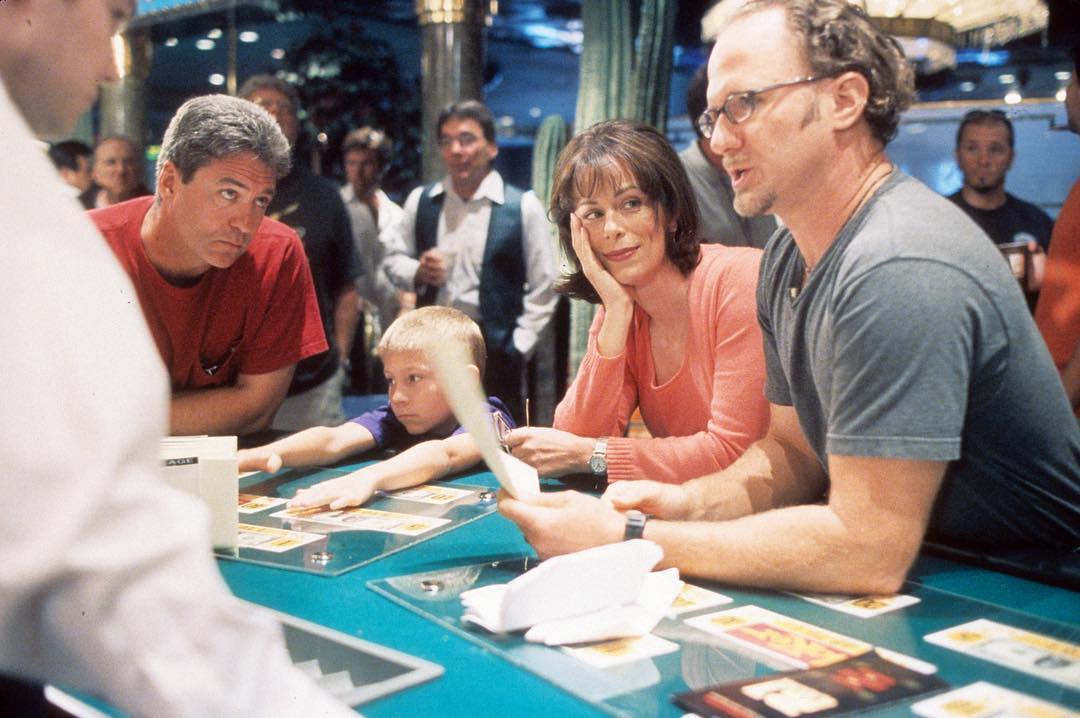

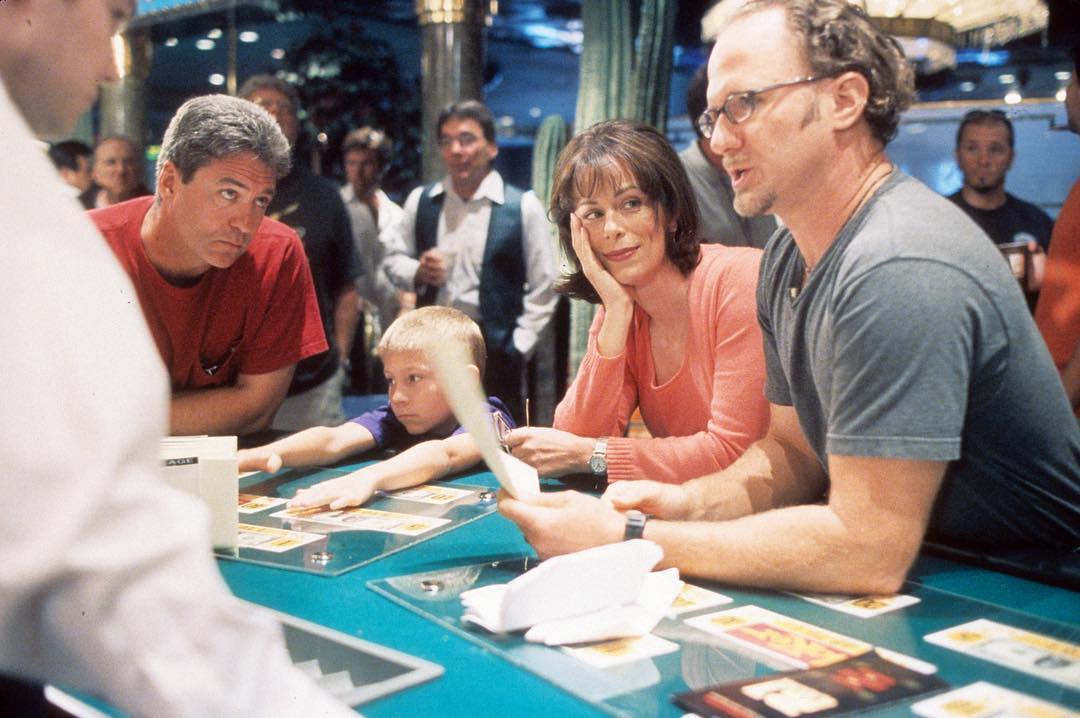

Todd Holland shooting 'Casino'

(photo Richard Foreman© 2000 Fox Broadcasting)

In 1998 Todd Holland was nominated for a DGA Award for his direction of the Emmy Award - winning episode "Flip" of HBO's The Larry Sanders Show. Added to his three previous Emmy nods for directing Sanders, the recognition from his DGA peers pretty much marked Holland's territory in the uppermost levels of comedy. Ironically, comedy was not the genre he'd envisioned when he got into directing. "I never watched comedy as a kid. I never liked comedy. I liked action thrillers and watched them over and over and dedicated my life to them and ended up here."

Whatever his proclivities, the fact remains that Todd Holland is very good at finding what's funny in a situation and capturing it on film. Recently he's been utilizing his talents on FOX's audience and critical hit Malcolm in the Middle. Even his DGA peers have noted the work as illustrated by director Gordon Hunt's response when someone at a Guild-sponsored seminar asked if he thought one-camera shows were funny, "Not until I saw Malcolm in the Middle."

For his direction of the Malcolm pilot, Holland earned his fifth Emmy nomination and recently spoke with DGA Magazine about Sanders, directing comedy and Malcolm in the Middle.

Why do you think you've been so successful as a comedy director?

I just did my very first bona fide thriller, the pilot for FreakyLinks. It's on FOX this fall. It was a chance to do something genuinely cinematic, visual and suspenseful. It was like 60% visual, 40% dialogue - very camera-driven, where the camera was a huge character in the piece.

I've wanted to do this kind of thing for 20 years and at first, I found I was less vigilant in directing suspense. Because I love it so much, I was too excited to be doing it. Fortunately I caught myself in time. That's when I realized; maybe I'm good at comedy because I'm very skeptical of it. I don't trust comedy to be funny. So I sit back and think, "OK,is that funny? No, this is funny." I believe you should challenge an audience to challenge you as someone presenting a show. You ought to work for that laugh and don't presume.

By your own admission you set out to be an action/thriller director. What happened?

Larry Sanders had this enormous dark side and yet it was incredibly funny and it was all about human behavior and I just got it. The road forked at that moment and comedy sort of begat comedy begat comedy.

But it's great to do comedy. As I've grown as a director, it's all become more about human behavior and the human experience, and comedy lets you go into that. Larry Sanders taught me to respect a genuine moment of human behavior and that anything is worth that.

I became notorious for what I call these "back to one" sequences where you do the full take, and everybody's struggling through their blocking ['blocking' is working out the movement and positioning of the actors as to be captured in the frame, often marked with tape] and having over-thought their moments. We'd get to the end and you do it at a certain moment where, cinematically, everything is starting to gel, then I just start screaming, "We're not cutting! We are going back to one! Back to one!" Everybody grabs their props, runs out the door and the cameras scramble to reset. Then I call "Action!" again before anybody has too much time to think.

Todd Holland shooting 'Casino'

(photo Richard Foreman© 2000 Fox Broadcasting)

What happens is, you get these remarkable performances and you don't have to talk a lot. If you've done your homework, everybody has what they need already. You don't need to tell the actors their motivation and the crew already knows what the shot's supposed to be. You just throw everyone into a momentary sense of letting go of all intellectualization and just do it. Actors love it because there's this weird sense of anticipation that leads up to, "OK. We are rolling. Quiet people. OK. Rolling. Sound." Then the actors stand there and wait while all this stuff builds and by the time you say, "Action!" they've had way too much time to think about the moment when you're going to say "Action!" When you throw them into momentary chaos, they just start talking and it's so often genuine.

What interested you in the Malcolm in the Middle pilot?

I read the pilot script and called [executive producer] Linwood Boomer and said, "There's an enormous amount of heart in this script. Is that an accident?" My fear of comedy is that it just goes for jokes. And he said, "It's absolutely intentional." And I said, "This sounds great. I would love to do this."

Again I've been very fortunate to stumble into that rare flavor of comedy that has enormous heart, enormous humanity, and yet can be raucously irreverent and wildly funny.

What do you think it was about your directing that caught Linwood's attention?

I think there's a connection between the dry honesty of Larry Sanders and this world. But Sanders is cinematically the antithesis of Malcolm in the Middle.

After doing 52 episodes of Sanders I had to re-learn a little bit about cinema because I got so used to doing "the camera cannot think" thing. On Sanders, the camera never starts on your shoe and comes up your leg to discover you in a conversation. That implies there's a sentient being behind the lens. The camera always was as if it just fell off a truck and just happened to be sitting there pointing and capturing a moment. So you lose all that sense of revealing a scene or dollying around a corner to discover something.

Malcolm is the opposite. We use every cinematic toy and device, lens, crane, StediCam, and the sky's the limit. Usually we're trying to figure out how to do things we don't even have tools for yet. You can totally control the audience's attention and play the comedy we do here at the pace we play it.

Directorially speaking, what makes a scene funny? Are there funny camera angles and lenses?

I've been watching what the other directors we have on Malcolm - Ken Kwapis, Jeff Melman and Arlene Sanford - do. I can see differences, particularly in Ken Kwapis. We shoot it in 16mm film, but Ken goes to the 16mm lens and I am always erring toward the 12mm. It actually adds a subtle, subtle shift. I think on a simplistic level comedy plays in space and that's why I tend to go a little closer and wider. I'm so impressed by the subtle precision of Ken's camerawork, but I've recognized my own personal style is innately a little wilder.

On Larry Sanders we tried to tighten up close-ups on one episode and make it a little more cinematic, and it wasn't as funny. You need to have nice, loose, medium shot kind of close-ups where you get body language. Comedy is about people in physical space. Suspense and drama are often about isolating faces in physical space. But comedy is all about the big wide frame and people passing through and loose close-ups and, you know, letting the moment exist in real time instead of doing it in pieces.

Todd Holland shooting 'Casino'

(photo Richard Foreman© 2000 Fox Broadcasting)

You're pulling double duty on Malcolm by executive producing as well as directing. Did you have much input into choosing the other directors?

When we got the pickup and they asked me to be a producer, the first name I set up was Ken Kwapis. I've been a huge fan of his work and I think he is very stylish and articulate. They all fell in love with Ken and now he's a producer/director on the show as well. Jeff Melman came in through Linwood and now we sort of have this very tiny little stable of talent that we go to and basically three of us are doing the season. There's like an odd episode where we're pulling from our tiny stable again, and filling that slot with Arlene Sanford.

How do you decide who directs which episodes?

This year, it's more about our schedules. We're doing 25 scripts and everything is on a fast track, so wherever we put ourselves on the schedule, you get the next script in line.

During the first season, we were so many scripts ahead I was able to fit myself into the ones that I thought I was suited for. I like character interaction-driven stories more than huge visual gags. This year, I'm getting a lot of the big visual gag stories, and part of that comes with being the senior person here. I keep thinking, isn't there a nice, simple little dinner-party scene or some dinner-party episode or something where it can all be about people. In my next episode the kids wander onto an artillery range, and we're literally doing a whole series of explosions. On the one I finished yesterday they build a gigantic slingshot on the roof of the house and they're launching things two city blocks. I had four kids on a set for a roof and they're just covered in slop and it was like, "You know, it should be easier than this. I just shot 60 scenes for a 21-minute show."

Considering the makeup of your show, the old adage about never working with kids cannot apply. But do you have any advice on the subject?

I've worked with kids for a long time. I did a movie in 1989 called The Wizard with Fred Savage. He was 12, just turning 13. I enjoy kids; that's why we typically get along. I understand that when they get into their teen years it gets harder. So I've always treated kids with respect and never talk down to them. I think kids are some of the smartest viewers we have. The best thing though is do not talk to kids as if they are kids. Talk to them as if they're people and they're equals to an extent. I mean there's always that point where you've got to tell everybody to shut up.

There was one horrifying moment for me on the pilot of Malcolm. I spent eight hours of an 11-hour shooting day on the playground trying to be Mr. Nice Guy with 110 11-year-old extras. "Come on, kids. You can do it. Come on." Finally, at one point they were just so loud and unruly I laid down the law and their faces all kind of went white. These are the extras I'm talking about. But, you know, almost every single one of them begged to come back the next day. They behaved so much better afterward. I realized that kids do this weird thing where though I never talk down to them, they need to know there is an authority figure. There is safety in that, I guess, if discipline, then safety.

We have incredible kids on the show; they're amazing. They're hard working, committed, but they are kids. They mess around and have fun on the set to some extent, but I have to tell you, it makes our set a nice place to be. The kids are smart and kind to each other and other people. They're respectful and the crew enjoys the energy of these kids on the set. It's a family experience.

Speaking of family, tell us about your AD [assistant director] teams.

David D'Ovidio and I go back to The Wizard where he was my 2nd AD. I heard he was 1st AD and we met and talked and all agreed that he'd be great.

Our other 1st AD last year, Steve Love, was an excellent first I did not know. He came in through our line producer and did a great job, but wasn't available this year so we bumped up one of our 2nd ADs, Cindy Potthast, to first.

A 1st AD relationship is such a personal relationship. To me, you're like a couple, you gotta' have energy that works on the set. I need someone who treats the crew the way I want to treat the crew - with respect. That's what I look for in an AD. I've never understood how people will abuse a crew or treat them badly and expect them to put out and really work for you.

Obviously, I want somebody who's organized, thinking ahead, and who's going to be a realist about scheduling. Sometimes I'm disappointed when an AD doesn't speak up when the work is greater than the schedule and no one's acknowledging that. But that's not a problem we have here.

Do all of your directors deliver their own cuts of the show?

Absolutely everyone does. We didn't have a deadline last year and I wanted everyone to be given the time to do the cuts that they believed in and turn them in to Linwood. To me, editing is half of directing. It's putting it together, feeling the pace of it, seeing if your choices worked and making sure that it works as well as it can. I wanted everyone else to have that opportunity as well.

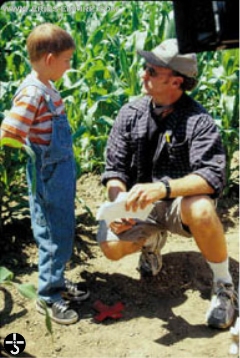

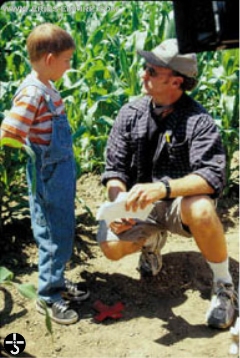

Todd Holland with Erik Per Sullivan (Dewey) shooting 'Traffic Jam'

(photo Carin Baer© 2000 Fox Broadcasting)

What would you like the DGA to be looking at?

Years ago on Larry Sanders, I decided to keep my own archive. I know the Guild is very involved in archiving and film preservation. So I started getting in my contract at HBO that I'd receive copies of all my Larry Sanders episodes on D-2 [professional digital video] at the time or Digi-Beta now. I got them at certain shows, which I won't name because I realize now sometimes I got them under-the-table from friendly producers. But now I'm trying to put it in my contracts to get Digi-Beta masters for my own personal archives. It's regarded as this broadcast-quality tape and they think that I'm now going to sell overseas or something, and the studios are saying "no, you get your three-quarter-inch tape." So I'm now trying to engineer in my deal some sort of agreement where I have access to a Digi-Beta master in perpetuity. I won't own it, but I'll be able to make whatever copies I ever want from it. I think it's a problem that's got to be addressed on some level if it's a director's right to maintain their own archives.

What do you think makes someone a good director?

It's a weird blend of hats. I really think you need to be a good listener. I listen to the actors, I listen to Linwood. I believe you listen and then make a decision. But to not listen is to cheat yourself of the wealth of wisdom and talent that is all around you on a set. I'm a big believer that every script of any value has a voice, and if you read it enough times and you listen closely enough, it will tell you where the camera goes and what it should be about and what's happening. You bring to it and add to it and contribute to it and change it and evolve it. I just read, read and read it over and over again. I come to the set on the weekends and I work on the blocking by myself and I just walk through it and I play all the characters and I figure out what's the scene about, where do I want to be. I plan and plan and plan. It gives me a chance to let go when I have to and rethink. But I need the safety net of a shot list and a plan and a tape.

I don't storyboard because, on movies they want them before you ever find the locations. By the time you find the locations, nothing about the storyboards really fits the locations and you're too close to production to redo them, so you've just got to pitch them out and work from a shot list. But I'm very spatial in my consciousness, so I can write it out verbally. And as long as I can figure out what the hell I meant when I wrote this shot down, then I can explain it to everybody else. And I tend to be very open with my crews.

Years ago, we started coming in half an hour before call - the DP [director of photography], the keys and the 1st - and we would walk through the day's work and say "Here's what we want to achieve today. Here are the shots, here's how it works." Malcolm and the shows I've done for the last few years have been great like that because we've had actors who saw the big comedy picture and didn't throw the whole thing into confusion with arguments over blocking. You can really plan ahead. And I believe a fully informed crew feels respected because you're giving them a chance to get ahead.

We did an episode last season called "Krelboyne Picnic" where there was a big science fair and we were in very short days late in the year, and had the kids in everything. Steve Love and I sat in his office and we went shot-by-shot and said, "OK, what do you think? Half an hour to get started, get the crew up on their feet. This first setup's going to take what, 45 minutes? Let's say an hour and 15 minutes. We can't afford that, let's say an hour. We'll get it in an hour." We tried to not be pessimistic and not be too optimistic. But we scheduled that show shot-by-shot for five days and then we handed it out to the crew and said, "Here is what we're doing." And we stayed shot-by-shot on schedule because we had to. Because of the rigors involved, the crew nicknamed that episode "The Von Krelboyne Express," but they really got into it because the timing was fair and we got the shots I wanted.

I don't give it to my producers. I give it to my 1st AD and the keys. Early in my career I have had producers who took my shot list and said, "How are you going to get this shot? You have to simplify." That's when you stop showing it to people. At a certain point you have to be respected as a responsible director who is working to make the schedule, but you're also working to make the show great. I know there are people who abuse schedules and are not responsible financially, but I don't happen to be one of them. So I just believe in fully informed people. I believe in planning ahead. I believe that makes a good director. That's my own fear-based system.

When you have had problems, like the one you just mentioned about the producers and your shot list, have you ever asked the Guild to help you out?

I've had situations where I needed the DGA to help me out. I read, I think it was your article on Thomas Schlamme and I've had the same situation, where it never occurred to me to call the DGA. But it also didn't occur to me to call my agent. I have subsequently learned to call the DGA when I have contractual problems or I feel I'm being disrespected, and it's sincerely the reason why I want to be more involved in the Guild. As I get older, I really have more and more respect for the reasons the Guild exists in the first place. The struggle for respect that directors went through and the courage to form the Guild in the first place, and just how sort of a cutthroat marketplace it is now in so many ways. The schedules are faster and the faster technology moves, the faster a director is supposed to move. And the reality is, this machine only goes so fast. A movie crew only moves so fast. Safely.

http://www.dga.org/news/v25_3/feat_todd.php3

Todd Holland

Keeping Malcolm in the Middle:

By Darrell L. Hope

Todd Holland shooting 'Casino'

(photo Richard Foreman© 2000 Fox Broadcasting)

In 1998 Todd Holland was nominated for a DGA Award for his direction of the Emmy Award - winning episode "Flip" of HBO's The Larry Sanders Show. Added to his three previous Emmy nods for directing Sanders, the recognition from his DGA peers pretty much marked Holland's territory in the uppermost levels of comedy. Ironically, comedy was not the genre he'd envisioned when he got into directing. "I never watched comedy as a kid. I never liked comedy. I liked action thrillers and watched them over and over and dedicated my life to them and ended up here."

Whatever his proclivities, the fact remains that Todd Holland is very good at finding what's funny in a situation and capturing it on film. Recently he's been utilizing his talents on FOX's audience and critical hit Malcolm in the Middle. Even his DGA peers have noted the work as illustrated by director Gordon Hunt's response when someone at a Guild-sponsored seminar asked if he thought one-camera shows were funny, "Not until I saw Malcolm in the Middle."

For his direction of the Malcolm pilot, Holland earned his fifth Emmy nomination and recently spoke with DGA Magazine about Sanders, directing comedy and Malcolm in the Middle.

Why do you think you've been so successful as a comedy director?

I just did my very first bona fide thriller, the pilot for FreakyLinks. It's on FOX this fall. It was a chance to do something genuinely cinematic, visual and suspenseful. It was like 60% visual, 40% dialogue - very camera-driven, where the camera was a huge character in the piece.

I've wanted to do this kind of thing for 20 years and at first, I found I was less vigilant in directing suspense. Because I love it so much, I was too excited to be doing it. Fortunately I caught myself in time. That's when I realized; maybe I'm good at comedy because I'm very skeptical of it. I don't trust comedy to be funny. So I sit back and think, "OK,is that funny? No, this is funny." I believe you should challenge an audience to challenge you as someone presenting a show. You ought to work for that laugh and don't presume.

By your own admission you set out to be an action/thriller director. What happened?

Larry Sanders had this enormous dark side and yet it was incredibly funny and it was all about human behavior and I just got it. The road forked at that moment and comedy sort of begat comedy begat comedy.

But it's great to do comedy. As I've grown as a director, it's all become more about human behavior and the human experience, and comedy lets you go into that. Larry Sanders taught me to respect a genuine moment of human behavior and that anything is worth that.

I became notorious for what I call these "back to one" sequences where you do the full take, and everybody's struggling through their blocking ['blocking' is working out the movement and positioning of the actors as to be captured in the frame, often marked with tape] and having over-thought their moments. We'd get to the end and you do it at a certain moment where, cinematically, everything is starting to gel, then I just start screaming, "We're not cutting! We are going back to one! Back to one!" Everybody grabs their props, runs out the door and the cameras scramble to reset. Then I call "Action!" again before anybody has too much time to think.

Todd Holland shooting 'Casino'

(photo Richard Foreman© 2000 Fox Broadcasting)

What happens is, you get these remarkable performances and you don't have to talk a lot. If you've done your homework, everybody has what they need already. You don't need to tell the actors their motivation and the crew already knows what the shot's supposed to be. You just throw everyone into a momentary sense of letting go of all intellectualization and just do it. Actors love it because there's this weird sense of anticipation that leads up to, "OK. We are rolling. Quiet people. OK. Rolling. Sound." Then the actors stand there and wait while all this stuff builds and by the time you say, "Action!" they've had way too much time to think about the moment when you're going to say "Action!" When you throw them into momentary chaos, they just start talking and it's so often genuine.

What interested you in the Malcolm in the Middle pilot?

I read the pilot script and called [executive producer] Linwood Boomer and said, "There's an enormous amount of heart in this script. Is that an accident?" My fear of comedy is that it just goes for jokes. And he said, "It's absolutely intentional." And I said, "This sounds great. I would love to do this."

Again I've been very fortunate to stumble into that rare flavor of comedy that has enormous heart, enormous humanity, and yet can be raucously irreverent and wildly funny.

What do you think it was about your directing that caught Linwood's attention?

I think there's a connection between the dry honesty of Larry Sanders and this world. But Sanders is cinematically the antithesis of Malcolm in the Middle.

After doing 52 episodes of Sanders I had to re-learn a little bit about cinema because I got so used to doing "the camera cannot think" thing. On Sanders, the camera never starts on your shoe and comes up your leg to discover you in a conversation. That implies there's a sentient being behind the lens. The camera always was as if it just fell off a truck and just happened to be sitting there pointing and capturing a moment. So you lose all that sense of revealing a scene or dollying around a corner to discover something.

Malcolm is the opposite. We use every cinematic toy and device, lens, crane, StediCam, and the sky's the limit. Usually we're trying to figure out how to do things we don't even have tools for yet. You can totally control the audience's attention and play the comedy we do here at the pace we play it.

Directorially speaking, what makes a scene funny? Are there funny camera angles and lenses?

I've been watching what the other directors we have on Malcolm - Ken Kwapis, Jeff Melman and Arlene Sanford - do. I can see differences, particularly in Ken Kwapis. We shoot it in 16mm film, but Ken goes to the 16mm lens and I am always erring toward the 12mm. It actually adds a subtle, subtle shift. I think on a simplistic level comedy plays in space and that's why I tend to go a little closer and wider. I'm so impressed by the subtle precision of Ken's camerawork, but I've recognized my own personal style is innately a little wilder.

On Larry Sanders we tried to tighten up close-ups on one episode and make it a little more cinematic, and it wasn't as funny. You need to have nice, loose, medium shot kind of close-ups where you get body language. Comedy is about people in physical space. Suspense and drama are often about isolating faces in physical space. But comedy is all about the big wide frame and people passing through and loose close-ups and, you know, letting the moment exist in real time instead of doing it in pieces.

Todd Holland shooting 'Casino'

(photo Richard Foreman© 2000 Fox Broadcasting)

You're pulling double duty on Malcolm by executive producing as well as directing. Did you have much input into choosing the other directors?

When we got the pickup and they asked me to be a producer, the first name I set up was Ken Kwapis. I've been a huge fan of his work and I think he is very stylish and articulate. They all fell in love with Ken and now he's a producer/director on the show as well. Jeff Melman came in through Linwood and now we sort of have this very tiny little stable of talent that we go to and basically three of us are doing the season. There's like an odd episode where we're pulling from our tiny stable again, and filling that slot with Arlene Sanford.

How do you decide who directs which episodes?

This year, it's more about our schedules. We're doing 25 scripts and everything is on a fast track, so wherever we put ourselves on the schedule, you get the next script in line.

During the first season, we were so many scripts ahead I was able to fit myself into the ones that I thought I was suited for. I like character interaction-driven stories more than huge visual gags. This year, I'm getting a lot of the big visual gag stories, and part of that comes with being the senior person here. I keep thinking, isn't there a nice, simple little dinner-party scene or some dinner-party episode or something where it can all be about people. In my next episode the kids wander onto an artillery range, and we're literally doing a whole series of explosions. On the one I finished yesterday they build a gigantic slingshot on the roof of the house and they're launching things two city blocks. I had four kids on a set for a roof and they're just covered in slop and it was like, "You know, it should be easier than this. I just shot 60 scenes for a 21-minute show."

Considering the makeup of your show, the old adage about never working with kids cannot apply. But do you have any advice on the subject?

I've worked with kids for a long time. I did a movie in 1989 called The Wizard with Fred Savage. He was 12, just turning 13. I enjoy kids; that's why we typically get along. I understand that when they get into their teen years it gets harder. So I've always treated kids with respect and never talk down to them. I think kids are some of the smartest viewers we have. The best thing though is do not talk to kids as if they are kids. Talk to them as if they're people and they're equals to an extent. I mean there's always that point where you've got to tell everybody to shut up.

There was one horrifying moment for me on the pilot of Malcolm. I spent eight hours of an 11-hour shooting day on the playground trying to be Mr. Nice Guy with 110 11-year-old extras. "Come on, kids. You can do it. Come on." Finally, at one point they were just so loud and unruly I laid down the law and their faces all kind of went white. These are the extras I'm talking about. But, you know, almost every single one of them begged to come back the next day. They behaved so much better afterward. I realized that kids do this weird thing where though I never talk down to them, they need to know there is an authority figure. There is safety in that, I guess, if discipline, then safety.

We have incredible kids on the show; they're amazing. They're hard working, committed, but they are kids. They mess around and have fun on the set to some extent, but I have to tell you, it makes our set a nice place to be. The kids are smart and kind to each other and other people. They're respectful and the crew enjoys the energy of these kids on the set. It's a family experience.

Speaking of family, tell us about your AD [assistant director] teams.

David D'Ovidio and I go back to The Wizard where he was my 2nd AD. I heard he was 1st AD and we met and talked and all agreed that he'd be great.

Our other 1st AD last year, Steve Love, was an excellent first I did not know. He came in through our line producer and did a great job, but wasn't available this year so we bumped up one of our 2nd ADs, Cindy Potthast, to first.

A 1st AD relationship is such a personal relationship. To me, you're like a couple, you gotta' have energy that works on the set. I need someone who treats the crew the way I want to treat the crew - with respect. That's what I look for in an AD. I've never understood how people will abuse a crew or treat them badly and expect them to put out and really work for you.

Obviously, I want somebody who's organized, thinking ahead, and who's going to be a realist about scheduling. Sometimes I'm disappointed when an AD doesn't speak up when the work is greater than the schedule and no one's acknowledging that. But that's not a problem we have here.

Do all of your directors deliver their own cuts of the show?

Absolutely everyone does. We didn't have a deadline last year and I wanted everyone to be given the time to do the cuts that they believed in and turn them in to Linwood. To me, editing is half of directing. It's putting it together, feeling the pace of it, seeing if your choices worked and making sure that it works as well as it can. I wanted everyone else to have that opportunity as well.

Todd Holland with Erik Per Sullivan (Dewey) shooting 'Traffic Jam'

(photo Carin Baer© 2000 Fox Broadcasting)

What would you like the DGA to be looking at?

Years ago on Larry Sanders, I decided to keep my own archive. I know the Guild is very involved in archiving and film preservation. So I started getting in my contract at HBO that I'd receive copies of all my Larry Sanders episodes on D-2 [professional digital video] at the time or Digi-Beta now. I got them at certain shows, which I won't name because I realize now sometimes I got them under-the-table from friendly producers. But now I'm trying to put it in my contracts to get Digi-Beta masters for my own personal archives. It's regarded as this broadcast-quality tape and they think that I'm now going to sell overseas or something, and the studios are saying "no, you get your three-quarter-inch tape." So I'm now trying to engineer in my deal some sort of agreement where I have access to a Digi-Beta master in perpetuity. I won't own it, but I'll be able to make whatever copies I ever want from it. I think it's a problem that's got to be addressed on some level if it's a director's right to maintain their own archives.

What do you think makes someone a good director?

It's a weird blend of hats. I really think you need to be a good listener. I listen to the actors, I listen to Linwood. I believe you listen and then make a decision. But to not listen is to cheat yourself of the wealth of wisdom and talent that is all around you on a set. I'm a big believer that every script of any value has a voice, and if you read it enough times and you listen closely enough, it will tell you where the camera goes and what it should be about and what's happening. You bring to it and add to it and contribute to it and change it and evolve it. I just read, read and read it over and over again. I come to the set on the weekends and I work on the blocking by myself and I just walk through it and I play all the characters and I figure out what's the scene about, where do I want to be. I plan and plan and plan. It gives me a chance to let go when I have to and rethink. But I need the safety net of a shot list and a plan and a tape.

I don't storyboard because, on movies they want them before you ever find the locations. By the time you find the locations, nothing about the storyboards really fits the locations and you're too close to production to redo them, so you've just got to pitch them out and work from a shot list. But I'm very spatial in my consciousness, so I can write it out verbally. And as long as I can figure out what the hell I meant when I wrote this shot down, then I can explain it to everybody else. And I tend to be very open with my crews.

Years ago, we started coming in half an hour before call - the DP [director of photography], the keys and the 1st - and we would walk through the day's work and say "Here's what we want to achieve today. Here are the shots, here's how it works." Malcolm and the shows I've done for the last few years have been great like that because we've had actors who saw the big comedy picture and didn't throw the whole thing into confusion with arguments over blocking. You can really plan ahead. And I believe a fully informed crew feels respected because you're giving them a chance to get ahead.

We did an episode last season called "Krelboyne Picnic" where there was a big science fair and we were in very short days late in the year, and had the kids in everything. Steve Love and I sat in his office and we went shot-by-shot and said, "OK, what do you think? Half an hour to get started, get the crew up on their feet. This first setup's going to take what, 45 minutes? Let's say an hour and 15 minutes. We can't afford that, let's say an hour. We'll get it in an hour." We tried to not be pessimistic and not be too optimistic. But we scheduled that show shot-by-shot for five days and then we handed it out to the crew and said, "Here is what we're doing." And we stayed shot-by-shot on schedule because we had to. Because of the rigors involved, the crew nicknamed that episode "The Von Krelboyne Express," but they really got into it because the timing was fair and we got the shots I wanted.

I don't give it to my producers. I give it to my 1st AD and the keys. Early in my career I have had producers who took my shot list and said, "How are you going to get this shot? You have to simplify." That's when you stop showing it to people. At a certain point you have to be respected as a responsible director who is working to make the schedule, but you're also working to make the show great. I know there are people who abuse schedules and are not responsible financially, but I don't happen to be one of them. So I just believe in fully informed people. I believe in planning ahead. I believe that makes a good director. That's my own fear-based system.

When you have had problems, like the one you just mentioned about the producers and your shot list, have you ever asked the Guild to help you out?

I've had situations where I needed the DGA to help me out. I read, I think it was your article on Thomas Schlamme and I've had the same situation, where it never occurred to me to call the DGA. But it also didn't occur to me to call my agent. I have subsequently learned to call the DGA when I have contractual problems or I feel I'm being disrespected, and it's sincerely the reason why I want to be more involved in the Guild. As I get older, I really have more and more respect for the reasons the Guild exists in the first place. The struggle for respect that directors went through and the courage to form the Guild in the first place, and just how sort of a cutthroat marketplace it is now in so many ways. The schedules are faster and the faster technology moves, the faster a director is supposed to move. And the reality is, this machine only goes so fast. A movie crew only moves so fast. Safely.

Last edited: