Richiepiep

Administrator

Hi all,

I just dug up this really nice, comprehensive and revealing article on Malcolm in the Middle's soundtrack composers They Might Be Giants from The New Yorker, August 12, 2002.

The original scans can be viewed here in our Gallery.

Here's the full text, bits on Malcolm highlighted:

John Flansburgh and John Linnell--partners in the musical duo They Might Be Giants--were on their way out of a trendy little restaurant in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, when the young waiter who had served them caught up to them. "You make good music," he said solemnly, then moved on. On the face of it, this was not a momentous event, but Flansburgh was beaming. "That was ABSOLUTELY flattering," he said as we arrived at the studio he maintains in his former apartment, a few blocks from the restaurant. "I think we've got a nice kind of fame."

They Might Be Giants have released nine albums in sixteen years, are about to issue a career-spanning boxed set, and have been touring since Reagan was in the White House. Two witty, articulate men in their early forties who write catchy songs about things like thermostats and metal detectors, Flansburgh and Linnell are the elders to a whole generation of smart, earnest "nerd rockers"--Moxy Fruvous, Barenaked Ladies, Harvey Danger, and Weezer, to name just a few. But, as highly respected, seminal bands often are, They Might Be Giants tend to be commercial runners-up to their offspring. (As David Bowie once put it, "It's not who does it first, it's who does it second.")

Still, it turns out, that's not such a bad thing. In an industry addicted to blockbusters, most bands don't rest in the middle ground for long; they either go on to greater things, or more often, drop back into obscurity. But They Might Be Giants, a band that's run like a grass-roots political campaign, has inhabited that rarified limbo for most of what Flansburgh calls their "tortoise-like career." The Giants gross between one and two million dollars a year, a sum that would barely cover Mariah Carey's manicure budget, but which, even after expenses, provides Flansburgh and Linnell with a tidy income and that most elusive of commodities artistic freedom. They probably won't ever get filthy rich, but they do earn a comfortable living doing exactly what they want to do, which makes them the envy of many far more commercially successful artists. Along with a select few--performers as disparate as Fugazi, Robyn Hitchcock, and Lucinda Williams--Flansburgh and Linnell enjoy a modest but constant popularity, the wonderful state of obscure success.

If a nerd is someone whose every word and deed are predicated on the belief that appearing smart is more important than getting laid, then They Might Be Giants are, in fact, nerds; their music doesn't sell sex; it sells smart-kid whimsy. Arty, melodic, and well wrought in a formal way, it bristles with wordplay and musical ideas. Its references are not to such totems of cool as the Velvet Underground and Leonard Cohen but to quirky styles ranging from polka and commercial country to cartoon music. So it's hardly surprising that They Might Be Giants have a disproportionately large presence on the Geek Broadcasting System, also known as the Internet. The Giants started a Web site back in 1994 and soon rivalled much more famous bands--Pearl Jam, U2, and Nirvana--in online popularity. Thanks to their Internet following, Linnell was voted one of People Online's ten most beautiful people in 1998, and at one point Flansburgh ranked high in the Person of the Century poll on Time's Web site, coming in just behind Jesus, Adolf Hitler, and the pro wrestler Ric Flair.

The two Johns long ago settled on a division of labor, or, as Linnell's wife, Karen Brown, puts it, "Flansburgh is Madonna and Linnell is Elton John." A natural musician, Linnell is the stronger singer and has written most of the duo's best-known songs, but he isn't keen on the hustling and schmoozing needed to pilot a band out of obscurity. "Linnell, if left to his own devices, would probably be writing brilliant music in his bedroom, and maybe his friends would hear it and go, 'Wow,'" the band's manager, Jamie Kitman, says. Linnell's nickname is the Professor and, in his customary pocket t-shirt and sneakers, he does have the benignly disheveled air of a graduate student. He is slight and flop-haired, and the heavy black glasses he sometimes wears sit crookedly on his nose. The last time I saw him, the glasses were held together with electrical tape, because his three-year-old son had given them a thrashing.

Whereas Linnell can seem aloof, Flansburgh is outgoing. With designer glasses, a precise haircut, and button-down shirts, he is a classic overachiever, supervising everything from stage backdrops to album covers. He hires and fires the road crew, meets with distributors and marketing executives, gives most of the interviews, and generally acts as the band's link to the outside world. He befriends artists, actors, and journalists, and shepherds through projects like the thirty-six tracks that the Giants recorded to accompany a recent issue of the literary journal, McSweeney's. Before a show, Flansburgh runs around dealing with last-minute details; Linnell often takes a nap.

Neither band member seems to resent the other for this arrangement, and so far it's worked very well. Not that either would complain if it hadn't. Kitman calls Flansburgh and Linnell "Yankee Puritans." He adds, "There's a part of them that's really Wasp. They don't say the things that we Jews would say to each other. People say, 'Get it out and then you can forgive each other.' Why even go there? If you don't say it, then you don't have to forgive it."

Flansburgh and Linnell grew up in the sixties and seventies in Lincoln, Massachusetts, an affluent, old-money Boston suburb that borders Walden Pond. "There's a New England trip that we were indoctrinated into," Flansburgh says, "a culture of grim-faced simplicity and work ethic and this direct relationship to everything that goes from the Pilgrim fathers right through Emerson."

Flansburgh's father runs a large architecture firm that specializes in building schools; his mother started the non-profit tour company Boston-by-Foot. Linnell's father is a psychiatrist; his mother is a poet. Both men say that the time and place they grew up in is perfectly encapsulated in their friend Rick Moody's novel "The Ice Storm." "All these people had made all this money, and they were in this green place in the woods in these modernistic cubes with really high-end jobs," Linnell says, "But they were growing sideburns and cheating on each other, going berserk. People of my generation saw it as kind of object lesson. The thing that I drew from it was actually more of an attitude of 'Get your shit together.'"

The two met while they were in high school, and started making recordings together, Linnell playing saxophone and keyboards while Flansburgh messed with a reel-to-reel tape deck. Both were paying close attention to Boston's WBCN, which was at the time a free-form radio station, whose d.j.s played not only the latest punk rock but also Miles Davis, "Mickey Mouse Club" songs, Firesign Theatre sketches, and George Jones. Linnell and Flansburgh had noticed the Beatles delving into music hall, tape collage, Indian classical, and Baroque; and, like most kids, they were bombarded with cartoon music, ad jingles, and TV themes. "Changing channels is our biggest tradition," Flansburgh once told a Spin reporter.

Linnell lasted a year at the University of Massachusetts before leaving to play with a New Wave band called the Mundanes, while Flansburgh bounced from school to school, teaching himself to play the guitar. On the same day in 1981, they both happened to move into a dilapidated Park Slope row house where a number of their high-school friends were living. They began playing music together again the following year, and they made their debut that summer, introduced as "El Grupo de Rock & Roll," at a Sandinista rally in Central Park. (They soon named themselves They Might Be Giants, after a 1971 film starring George C. Scott.) Flansburgh, on guitar, and Linnell, on accordion--the instrument became a hallmark of the band--played as a duo mostly because they had little chance of finding anyone else who thought the way they did; besides, they made more by dividing the money only two ways. Their "backing band" was a tape deck that played homemade samplings of a Moog synthesizer, a drum machine, Music Minus One records, tape loops, and old rhythm machines that wheezed out foxtrots and rhumbas.

Although the punk scene that had originally attracted the two to New York was already a fading memory, cheap rents allowed artists to stay in the city, and East Village clubs began to host a kind of postmodern vaudeville, featuring a new genre called performance art. It was the perfect place for a band that sported song titles like "Boat of Car" and "Youth Culture Killed My Dog," and They Might Be Giants began to build up a following at underground clubs like 8 B.C., Darinka, and Neither/Nor. Fellow-musicians such as Laurie Anderson, Frank Maya, and even Talking Heads were using performance-art-inspired props. Linnell and Flansburgh wore papier-mache monster hands and outsized fezzes and banged an amplified tree branch on the stage floor. They once invited everyone in the audience to bring an instrument to a performance at the Pyramid Club, where transvestite waiters served Blue Whales and about a hundred people wielding acoustic guitars played "Mr. Tambourine Man" along with the band. Soon, the Giants were appearing on bills with performers ranging from Ann Magnuson and Steve Buscemi to a young man with no arms who walked onstage in a dress and stripped naked as another man counted backward from a hundred in German.

They Might Be Giants were also developing what the music industry now calls, "alternative marketing strategies." Their first release, in early 1985, was a flexi-disk, a floppy plastic record usually stapled into magazines, which they sold via mail order, handed out at shows, and sometimes nailed to trees in Tompkins Square Park. Two years earlier, they'd transferred some recordings they'd made to their telephone answering machine, which was then a novel piece of technology. They advertised the resulting "Dial-a-Song" phone line-which they still run, with a new song nearly every day, at (718)387-6962-in the Village Voice. In a way, Dial-a-Song was a prototype for streaming audio on the Internet--a readily-accesible music-delivery system. True, the Giants didn't make any money from it (when Paula Abdul and New Kids on the Block followed suit, years later, they used 900 numbers), but it established a personal, everyday connection with their fans. Virtually all of the several hundred songs that Flansburgh and Linnell have recorded have played, in various states of completion, on Dial-a-Song; low-tech, low-cost, and astonishingly effective, it remains one of the key ways in which people are introduced to the band.

In 1983, Jamie Kitman was preparing for a career as a lawyer when a friend took him to a seedy downtown club to see They Might Be Giants. A former Spy magazine contributor and political consultant, Kitman helped They Might Be Giants attract a following beyond the East Village, and soon the clubs they played were full of young people with media jobs in midtown who were just catching on to the performance-art scene. "They Might Be Giants were the kind of experience that wasn't only for your serious performance-art junkies," Kitman says. "You could take your friends from out of town, and it wasn't like you'd be watching paint dry or somebody getting his skin ripped off."

By the summer of 1986, the buzz had reached the offices of People, which gave a rave review to a twenty-three-song cassette the band was selling. The Giants had a video too. Directed by the fledgling auteur Adam Bernstein, "Put Your Hand Inside the Puppet Head" was shot for only a few hundred dollars. The low-budget clip had a jittery energy: while Robert Palmer, in his videos, was crooning in designer suits, surrounded by automatronic beauties, They Might Be Giants wore ill-fitting thrift-shop clothes and danced on the garbage-strewn waterfront of Williamsburg.

Since 1983, the Giants had been recording songs at tiny Manhattan studios in the middle of the night, when the rates were lowest and no one would notice if they ran overtime. When their eponymous debut album came out, in late 1986, on Bar/None, a record label based in Hoboken, New Jersey, the music had the intimate quality of a home recording. It was constructed almost entirely of synthetic sounds, partly in homage to the proletarian dance music that blasted from open windows and car stereos in Fort Greene, where Linnell and Flansburgh were living then. A drum machine gave the music a campy, herky-jerky feel, and the two men sang in heraldic, nasal tones that recalled the Phil Ochs records that Flansburgh had grown up listening to. What fired They Might Be Giants' art was not so much emotional yearning as the craft of songwriting itself. "I think our songwriting has tried to deal with some very subtle, almost aesthetic ideas that are well beyond writing a lyric about romance," Flansburgh says. The lyrics of the songs on that first album, as on most of those which followed, were profoundly enigmatic. (There is a Web site devoted to fans' often far-reaching interpretations of Giants lyrics; " 'Particle Man' concerns the nature of the life, the universe and everything," goes one line of thought. " 'Triangle Man' has also been interpreted to represent change, religion, the homosexual community, and is a reference to a quantum physics phenomenon as well.")

They Might Be Giants toured in support of the album for about a year. Money was tight, so Kitman, who did freelance articles for the magazine Automobile, finagled an assignment to road-test a Plymouth Voyager--the first minivan--on the Giants' nineteen-city, fifty-two-hundred-mile "Bring Me the Head of Kenny Rogers World Tour '87." When the band played Pittsburgh's now defunct Electric Banana, there were only twenty-seven people in the club, and Kitman was deeply discouraged. "I was saying, 'Let's just go home,' and the Giants were saying, 'No, no,'" he recalls. "And they went out and shook everybody's hand in the audience and then played the best show I'd ever seen them play." One member of the audience was a programming executive for a local radio station, WXDX; the next day, WXDX became the first commercial station in the country to add They Might Be Giants to its playlist. The single "Don't Let's Start" later became a hit on the influential K-Rock station in Los Angeles, and Bar/None struggled to keep up with demand for the record. Adam Bernstein shot a video for "Don't Let's Start," and in January of 1988 it became one of the first independent-label videos to air regularly on MTV. Sales of the album exploded, going from around a thousand a month to about fifty thousand the month the video entered heavy rotation.

In May of 1990, as the lights went down before a They Might Be Giants show at the Beacon Theatre, in New York, there was a faint high-pitched sound--perhaps an amplifier onstage was feeding back. As it got louder, it began to resemble the whine of a jet plane. And then, suddenly, it became clear what the sound was: thousands of girls screaming for John and John. In the spring of that year, the band had scored a surprise Top Five hit in the U.K. with "Birdhouse in Your Soul," an anthemic number told from the point of view of an emotionally needy night-light. And after the release, the previous January, of "Flood," the band's third album, and its first for a major label, Elektra, the Giants had begun to tour relentlessly, in order to generate interest in the next album, which was expected to be their breakthrough in the United States.

In the event, "Apollo 18," which came out in 1992, failed to yield a hit, and the screaming girls had moved on to other bands. Since the release of "Flood," more aggressive grunge bands like Nirvana and Pearl Jam had come along and redefined the industry's idea of what was marketable, and many of the Giants' supporters at Elektra were leaving the company. "All of a sudden, people weren't happy to see us," Kitman recalls. "They were already saying, 'O.K., time's up.'" Elektra lent lacklustre support to the next two albums, and the band and the label parted ways in 1997. At this point, many groups would have given up, but Flansburgh and Linnell simply got back to work and started looking for innovative ways to stay afloat.

One of the first things they tried was the fledgling idea of Internet distribution. The band's "Long Tall Weekend," which sold more than twenty-five thousand copies through eMusic.com, became the most downloaded-for-pay album ever. Flansburgh shrugs off this accomplishment, saying that it's "like being the world's tallest midget," since any major-label band that sold so few copies would get dropped. But They Might Be Giants were successful pioneers. "They proved that downloadable music could be sold on the Internet," Jim Stabile, who was then eMusic's director of artist relations, says. Since the band rarely gets played on the radio or MTV these days, the availability of its songs online is still a major component of its popularity--fans share the music with friends via e-mail, thereby multiplying the band's following. The Giants first grasped the power of the Internet on tour, when audiences began applauding the opening notes of songs that hadn't been released on CD yet.

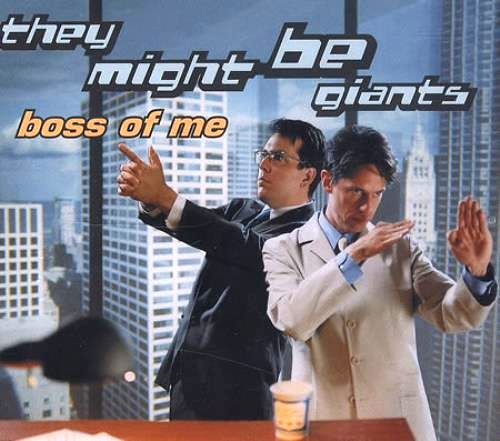

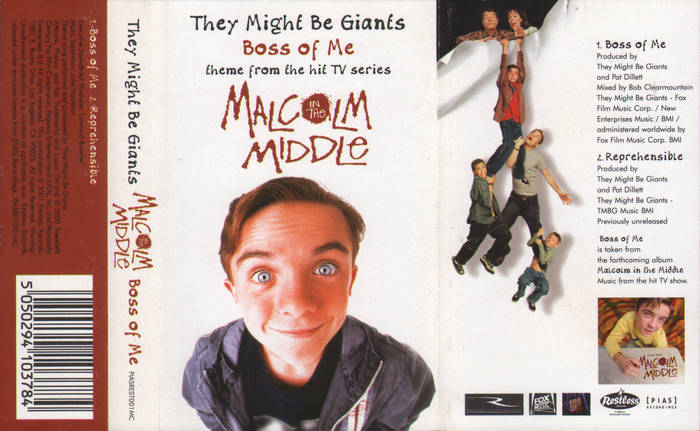

The band remains a big draw on the college circuit; at university shows, there are inevitably seventeen guys in the audience with "T-H-E-Y-M-I-G-H-T-B-E-G-I-A-N-T-S" painted on their bare chests. "They tie in to some pubescent, smart-kid mind-set, and it's a perennial," Glenn Morrow, the co-owner of Bar/None Records, says. "They're Pied Pipers for those kids." The band has been going for so long that many of the bright kids who discovered it in college have now assumed positions of power, particularly in the media. When the band wrote the song, "Dr. Evil," for "Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me," in 1999, the film's co-producer and star, Mike Myers, a long-time fan, insisted on placing it in the opening scene. Flansburgh and Linnell were then introduced to another admirer, Linwood Boomer, the creator of the sitcom, "Malcolm in the Middle," who asked if they'd be interested in doing a theme song for the new show; Flansburgh offered to write the incidental music, too, and he and Linnell spent the better part of the next two years working up an episode's worth of music every week. They provided music for "The Daily Show," hosted by Jon Stewart, whom they'd known since he was a bartender at the City Gardens club, in Trenton, New Jersey. And Linnell's birthday was recently announced on Fox News, clearly because the band had a fan on the staff.

They Might Be Giants have also broken into the world of advertising, making music for Coca-Cola, Diet Dr. Pepper, Chrysler, and Weber grills. And they have recorded a children's album, called "No!," complete with charming interactive content, which was released this June and hit the top of the Billboard kid's chart. "No!" was an artistic breakthrough, taking the band back to the vocal-intensive, sound-driven approach of its early years, a reversion that had an appealing influence on last fall's "Mink Car," its most recent album for adults.

Last summer, They Might Be Giants played a mini-tour, the kind of low-key trip that helps a band like theirs keep going between albums. The first stop was the Fourth Annual Sunset Music Festival in Newport, Rhode Island, where other artists included mellow baby boomers like David Crosby and Livingston Taylor. It wasn't the hippest gig, but then ones that pay the bills rarely are.

In the bright sunshine outside the band's trailer stood Nathaniel, a sixteen-year-old with a patch of bleached hair and a green camouflage T-shirt spiffed up with a skinny tie; his friend Chris had glasses, braces, and a skinny tie of his own. What drew them to They Might Be Giants? I asked. "They sing about Presidents and 'Planet of the Apes,'" Nathaniel explained. "It's not all about girls." "I think there should be a dork-rock tour of Weezer, They Might Be Giants, and Harvey Danger," Chris exclaimed, apropos of nothing in particular. "That'd be awesome! A whole crowd of people just like me!"

Despite fans like these, things weren't going in the Giants' favor that night: only about nine hundred people had bought tickets to a venue that holds twice that number, the police hassled the soundman about the decibel level, and someone kept flipping on the house lights. But eventually a few brave souls got up to dance; others joined in, and suddenly there was a dance party right in front of the stage. "Last night was a victory," Flansburgh pronounced the next morning at the Providence airport. "Here's to perseverance."

Their next gig, a free outdoor show in Nashville, was much more successful. Some fifteen thousand people watched the band pump out a strong performance on a barge tethered to the shore of the Cumberland River. Afterward Flansburgh did a meet-and-greet session with fans, off to the side of the stage, as he has done since the band started. He worked a long line--at least a hundred people--like a politician, tirelessly shaking hands, signing autographs, getting his picture taken with smiling fans, enthusiastically answering questions about the band. He stayed until he had met everybody--well over an hour. As the last people in line, a couple of twenty-something guys, strolled off into the night, Flansburgh called out, "See ya in the pit, fellas!"

The Giants will probably never play to audiences this size on a regular basis, but that's O.K. with them. Sales of "Mink Car" suffered because it happened to be released on September 11th, and shortly afterward their current label, Restless, drastically reorganized. But, in many ways, things have never been better for Flansburgh and Linnell: the theme song from "Malcolm in the Middle" won a Grammy this year; they are the subject of a full-length documentary called "Gigantic (A Tale of Two Johns)"; and on August 15th they'll be playing a twentieth-anniversary show at Central Park's SummerStage, a stone's throw from the spot where they made their debut. (This time, they won't have to carry their equipment over a stone wall.) "We lowered our expectations right away," Flansburgh says. "That's been very useful in having an enduring career in rock." He adds, "Is this a good enough life for us? I think the answer is pretty clear: yeah. We roll down the road with people cheering as the bus pulls away. There are a lot of harder things to do in the world."

I just dug up this really nice, comprehensive and revealing article on Malcolm in the Middle's soundtrack composers They Might Be Giants from The New Yorker, August 12, 2002.

The original scans can be viewed here in our Gallery.

Here's the full text, bits on Malcolm highlighted:

Urban Legends

The do-it-yourself success of They Might Be Giants

The New Yorker, August 12, 2002

By Michael Azerrad

The do-it-yourself success of They Might Be Giants

The New Yorker, August 12, 2002

By Michael Azerrad

John Flansburgh and John Linnell--partners in the musical duo They Might Be Giants--were on their way out of a trendy little restaurant in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, when the young waiter who had served them caught up to them. "You make good music," he said solemnly, then moved on. On the face of it, this was not a momentous event, but Flansburgh was beaming. "That was ABSOLUTELY flattering," he said as we arrived at the studio he maintains in his former apartment, a few blocks from the restaurant. "I think we've got a nice kind of fame."

They Might Be Giants have released nine albums in sixteen years, are about to issue a career-spanning boxed set, and have been touring since Reagan was in the White House. Two witty, articulate men in their early forties who write catchy songs about things like thermostats and metal detectors, Flansburgh and Linnell are the elders to a whole generation of smart, earnest "nerd rockers"--Moxy Fruvous, Barenaked Ladies, Harvey Danger, and Weezer, to name just a few. But, as highly respected, seminal bands often are, They Might Be Giants tend to be commercial runners-up to their offspring. (As David Bowie once put it, "It's not who does it first, it's who does it second.")

Still, it turns out, that's not such a bad thing. In an industry addicted to blockbusters, most bands don't rest in the middle ground for long; they either go on to greater things, or more often, drop back into obscurity. But They Might Be Giants, a band that's run like a grass-roots political campaign, has inhabited that rarified limbo for most of what Flansburgh calls their "tortoise-like career." The Giants gross between one and two million dollars a year, a sum that would barely cover Mariah Carey's manicure budget, but which, even after expenses, provides Flansburgh and Linnell with a tidy income and that most elusive of commodities artistic freedom. They probably won't ever get filthy rich, but they do earn a comfortable living doing exactly what they want to do, which makes them the envy of many far more commercially successful artists. Along with a select few--performers as disparate as Fugazi, Robyn Hitchcock, and Lucinda Williams--Flansburgh and Linnell enjoy a modest but constant popularity, the wonderful state of obscure success.

If a nerd is someone whose every word and deed are predicated on the belief that appearing smart is more important than getting laid, then They Might Be Giants are, in fact, nerds; their music doesn't sell sex; it sells smart-kid whimsy. Arty, melodic, and well wrought in a formal way, it bristles with wordplay and musical ideas. Its references are not to such totems of cool as the Velvet Underground and Leonard Cohen but to quirky styles ranging from polka and commercial country to cartoon music. So it's hardly surprising that They Might Be Giants have a disproportionately large presence on the Geek Broadcasting System, also known as the Internet. The Giants started a Web site back in 1994 and soon rivalled much more famous bands--Pearl Jam, U2, and Nirvana--in online popularity. Thanks to their Internet following, Linnell was voted one of People Online's ten most beautiful people in 1998, and at one point Flansburgh ranked high in the Person of the Century poll on Time's Web site, coming in just behind Jesus, Adolf Hitler, and the pro wrestler Ric Flair.

The two Johns long ago settled on a division of labor, or, as Linnell's wife, Karen Brown, puts it, "Flansburgh is Madonna and Linnell is Elton John." A natural musician, Linnell is the stronger singer and has written most of the duo's best-known songs, but he isn't keen on the hustling and schmoozing needed to pilot a band out of obscurity. "Linnell, if left to his own devices, would probably be writing brilliant music in his bedroom, and maybe his friends would hear it and go, 'Wow,'" the band's manager, Jamie Kitman, says. Linnell's nickname is the Professor and, in his customary pocket t-shirt and sneakers, he does have the benignly disheveled air of a graduate student. He is slight and flop-haired, and the heavy black glasses he sometimes wears sit crookedly on his nose. The last time I saw him, the glasses were held together with electrical tape, because his three-year-old son had given them a thrashing.

Whereas Linnell can seem aloof, Flansburgh is outgoing. With designer glasses, a precise haircut, and button-down shirts, he is a classic overachiever, supervising everything from stage backdrops to album covers. He hires and fires the road crew, meets with distributors and marketing executives, gives most of the interviews, and generally acts as the band's link to the outside world. He befriends artists, actors, and journalists, and shepherds through projects like the thirty-six tracks that the Giants recorded to accompany a recent issue of the literary journal, McSweeney's. Before a show, Flansburgh runs around dealing with last-minute details; Linnell often takes a nap.

Neither band member seems to resent the other for this arrangement, and so far it's worked very well. Not that either would complain if it hadn't. Kitman calls Flansburgh and Linnell "Yankee Puritans." He adds, "There's a part of them that's really Wasp. They don't say the things that we Jews would say to each other. People say, 'Get it out and then you can forgive each other.' Why even go there? If you don't say it, then you don't have to forgive it."

Flansburgh and Linnell grew up in the sixties and seventies in Lincoln, Massachusetts, an affluent, old-money Boston suburb that borders Walden Pond. "There's a New England trip that we were indoctrinated into," Flansburgh says, "a culture of grim-faced simplicity and work ethic and this direct relationship to everything that goes from the Pilgrim fathers right through Emerson."

Flansburgh's father runs a large architecture firm that specializes in building schools; his mother started the non-profit tour company Boston-by-Foot. Linnell's father is a psychiatrist; his mother is a poet. Both men say that the time and place they grew up in is perfectly encapsulated in their friend Rick Moody's novel "The Ice Storm." "All these people had made all this money, and they were in this green place in the woods in these modernistic cubes with really high-end jobs," Linnell says, "But they were growing sideburns and cheating on each other, going berserk. People of my generation saw it as kind of object lesson. The thing that I drew from it was actually more of an attitude of 'Get your shit together.'"

The two met while they were in high school, and started making recordings together, Linnell playing saxophone and keyboards while Flansburgh messed with a reel-to-reel tape deck. Both were paying close attention to Boston's WBCN, which was at the time a free-form radio station, whose d.j.s played not only the latest punk rock but also Miles Davis, "Mickey Mouse Club" songs, Firesign Theatre sketches, and George Jones. Linnell and Flansburgh had noticed the Beatles delving into music hall, tape collage, Indian classical, and Baroque; and, like most kids, they were bombarded with cartoon music, ad jingles, and TV themes. "Changing channels is our biggest tradition," Flansburgh once told a Spin reporter.

Linnell lasted a year at the University of Massachusetts before leaving to play with a New Wave band called the Mundanes, while Flansburgh bounced from school to school, teaching himself to play the guitar. On the same day in 1981, they both happened to move into a dilapidated Park Slope row house where a number of their high-school friends were living. They began playing music together again the following year, and they made their debut that summer, introduced as "El Grupo de Rock & Roll," at a Sandinista rally in Central Park. (They soon named themselves They Might Be Giants, after a 1971 film starring George C. Scott.) Flansburgh, on guitar, and Linnell, on accordion--the instrument became a hallmark of the band--played as a duo mostly because they had little chance of finding anyone else who thought the way they did; besides, they made more by dividing the money only two ways. Their "backing band" was a tape deck that played homemade samplings of a Moog synthesizer, a drum machine, Music Minus One records, tape loops, and old rhythm machines that wheezed out foxtrots and rhumbas.

Although the punk scene that had originally attracted the two to New York was already a fading memory, cheap rents allowed artists to stay in the city, and East Village clubs began to host a kind of postmodern vaudeville, featuring a new genre called performance art. It was the perfect place for a band that sported song titles like "Boat of Car" and "Youth Culture Killed My Dog," and They Might Be Giants began to build up a following at underground clubs like 8 B.C., Darinka, and Neither/Nor. Fellow-musicians such as Laurie Anderson, Frank Maya, and even Talking Heads were using performance-art-inspired props. Linnell and Flansburgh wore papier-mache monster hands and outsized fezzes and banged an amplified tree branch on the stage floor. They once invited everyone in the audience to bring an instrument to a performance at the Pyramid Club, where transvestite waiters served Blue Whales and about a hundred people wielding acoustic guitars played "Mr. Tambourine Man" along with the band. Soon, the Giants were appearing on bills with performers ranging from Ann Magnuson and Steve Buscemi to a young man with no arms who walked onstage in a dress and stripped naked as another man counted backward from a hundred in German.

They Might Be Giants were also developing what the music industry now calls, "alternative marketing strategies." Their first release, in early 1985, was a flexi-disk, a floppy plastic record usually stapled into magazines, which they sold via mail order, handed out at shows, and sometimes nailed to trees in Tompkins Square Park. Two years earlier, they'd transferred some recordings they'd made to their telephone answering machine, which was then a novel piece of technology. They advertised the resulting "Dial-a-Song" phone line-which they still run, with a new song nearly every day, at (718)387-6962-in the Village Voice. In a way, Dial-a-Song was a prototype for streaming audio on the Internet--a readily-accesible music-delivery system. True, the Giants didn't make any money from it (when Paula Abdul and New Kids on the Block followed suit, years later, they used 900 numbers), but it established a personal, everyday connection with their fans. Virtually all of the several hundred songs that Flansburgh and Linnell have recorded have played, in various states of completion, on Dial-a-Song; low-tech, low-cost, and astonishingly effective, it remains one of the key ways in which people are introduced to the band.

In 1983, Jamie Kitman was preparing for a career as a lawyer when a friend took him to a seedy downtown club to see They Might Be Giants. A former Spy magazine contributor and political consultant, Kitman helped They Might Be Giants attract a following beyond the East Village, and soon the clubs they played were full of young people with media jobs in midtown who were just catching on to the performance-art scene. "They Might Be Giants were the kind of experience that wasn't only for your serious performance-art junkies," Kitman says. "You could take your friends from out of town, and it wasn't like you'd be watching paint dry or somebody getting his skin ripped off."

By the summer of 1986, the buzz had reached the offices of People, which gave a rave review to a twenty-three-song cassette the band was selling. The Giants had a video too. Directed by the fledgling auteur Adam Bernstein, "Put Your Hand Inside the Puppet Head" was shot for only a few hundred dollars. The low-budget clip had a jittery energy: while Robert Palmer, in his videos, was crooning in designer suits, surrounded by automatronic beauties, They Might Be Giants wore ill-fitting thrift-shop clothes and danced on the garbage-strewn waterfront of Williamsburg.

Since 1983, the Giants had been recording songs at tiny Manhattan studios in the middle of the night, when the rates were lowest and no one would notice if they ran overtime. When their eponymous debut album came out, in late 1986, on Bar/None, a record label based in Hoboken, New Jersey, the music had the intimate quality of a home recording. It was constructed almost entirely of synthetic sounds, partly in homage to the proletarian dance music that blasted from open windows and car stereos in Fort Greene, where Linnell and Flansburgh were living then. A drum machine gave the music a campy, herky-jerky feel, and the two men sang in heraldic, nasal tones that recalled the Phil Ochs records that Flansburgh had grown up listening to. What fired They Might Be Giants' art was not so much emotional yearning as the craft of songwriting itself. "I think our songwriting has tried to deal with some very subtle, almost aesthetic ideas that are well beyond writing a lyric about romance," Flansburgh says. The lyrics of the songs on that first album, as on most of those which followed, were profoundly enigmatic. (There is a Web site devoted to fans' often far-reaching interpretations of Giants lyrics; " 'Particle Man' concerns the nature of the life, the universe and everything," goes one line of thought. " 'Triangle Man' has also been interpreted to represent change, religion, the homosexual community, and is a reference to a quantum physics phenomenon as well.")

They Might Be Giants toured in support of the album for about a year. Money was tight, so Kitman, who did freelance articles for the magazine Automobile, finagled an assignment to road-test a Plymouth Voyager--the first minivan--on the Giants' nineteen-city, fifty-two-hundred-mile "Bring Me the Head of Kenny Rogers World Tour '87." When the band played Pittsburgh's now defunct Electric Banana, there were only twenty-seven people in the club, and Kitman was deeply discouraged. "I was saying, 'Let's just go home,' and the Giants were saying, 'No, no,'" he recalls. "And they went out and shook everybody's hand in the audience and then played the best show I'd ever seen them play." One member of the audience was a programming executive for a local radio station, WXDX; the next day, WXDX became the first commercial station in the country to add They Might Be Giants to its playlist. The single "Don't Let's Start" later became a hit on the influential K-Rock station in Los Angeles, and Bar/None struggled to keep up with demand for the record. Adam Bernstein shot a video for "Don't Let's Start," and in January of 1988 it became one of the first independent-label videos to air regularly on MTV. Sales of the album exploded, going from around a thousand a month to about fifty thousand the month the video entered heavy rotation.

In May of 1990, as the lights went down before a They Might Be Giants show at the Beacon Theatre, in New York, there was a faint high-pitched sound--perhaps an amplifier onstage was feeding back. As it got louder, it began to resemble the whine of a jet plane. And then, suddenly, it became clear what the sound was: thousands of girls screaming for John and John. In the spring of that year, the band had scored a surprise Top Five hit in the U.K. with "Birdhouse in Your Soul," an anthemic number told from the point of view of an emotionally needy night-light. And after the release, the previous January, of "Flood," the band's third album, and its first for a major label, Elektra, the Giants had begun to tour relentlessly, in order to generate interest in the next album, which was expected to be their breakthrough in the United States.

In the event, "Apollo 18," which came out in 1992, failed to yield a hit, and the screaming girls had moved on to other bands. Since the release of "Flood," more aggressive grunge bands like Nirvana and Pearl Jam had come along and redefined the industry's idea of what was marketable, and many of the Giants' supporters at Elektra were leaving the company. "All of a sudden, people weren't happy to see us," Kitman recalls. "They were already saying, 'O.K., time's up.'" Elektra lent lacklustre support to the next two albums, and the band and the label parted ways in 1997. At this point, many groups would have given up, but Flansburgh and Linnell simply got back to work and started looking for innovative ways to stay afloat.

One of the first things they tried was the fledgling idea of Internet distribution. The band's "Long Tall Weekend," which sold more than twenty-five thousand copies through eMusic.com, became the most downloaded-for-pay album ever. Flansburgh shrugs off this accomplishment, saying that it's "like being the world's tallest midget," since any major-label band that sold so few copies would get dropped. But They Might Be Giants were successful pioneers. "They proved that downloadable music could be sold on the Internet," Jim Stabile, who was then eMusic's director of artist relations, says. Since the band rarely gets played on the radio or MTV these days, the availability of its songs online is still a major component of its popularity--fans share the music with friends via e-mail, thereby multiplying the band's following. The Giants first grasped the power of the Internet on tour, when audiences began applauding the opening notes of songs that hadn't been released on CD yet.

The band remains a big draw on the college circuit; at university shows, there are inevitably seventeen guys in the audience with "T-H-E-Y-M-I-G-H-T-B-E-G-I-A-N-T-S" painted on their bare chests. "They tie in to some pubescent, smart-kid mind-set, and it's a perennial," Glenn Morrow, the co-owner of Bar/None Records, says. "They're Pied Pipers for those kids." The band has been going for so long that many of the bright kids who discovered it in college have now assumed positions of power, particularly in the media. When the band wrote the song, "Dr. Evil," for "Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me," in 1999, the film's co-producer and star, Mike Myers, a long-time fan, insisted on placing it in the opening scene. Flansburgh and Linnell were then introduced to another admirer, Linwood Boomer, the creator of the sitcom, "Malcolm in the Middle," who asked if they'd be interested in doing a theme song for the new show; Flansburgh offered to write the incidental music, too, and he and Linnell spent the better part of the next two years working up an episode's worth of music every week. They provided music for "The Daily Show," hosted by Jon Stewart, whom they'd known since he was a bartender at the City Gardens club, in Trenton, New Jersey. And Linnell's birthday was recently announced on Fox News, clearly because the band had a fan on the staff.

They Might Be Giants have also broken into the world of advertising, making music for Coca-Cola, Diet Dr. Pepper, Chrysler, and Weber grills. And they have recorded a children's album, called "No!," complete with charming interactive content, which was released this June and hit the top of the Billboard kid's chart. "No!" was an artistic breakthrough, taking the band back to the vocal-intensive, sound-driven approach of its early years, a reversion that had an appealing influence on last fall's "Mink Car," its most recent album for adults.

Last summer, They Might Be Giants played a mini-tour, the kind of low-key trip that helps a band like theirs keep going between albums. The first stop was the Fourth Annual Sunset Music Festival in Newport, Rhode Island, where other artists included mellow baby boomers like David Crosby and Livingston Taylor. It wasn't the hippest gig, but then ones that pay the bills rarely are.

In the bright sunshine outside the band's trailer stood Nathaniel, a sixteen-year-old with a patch of bleached hair and a green camouflage T-shirt spiffed up with a skinny tie; his friend Chris had glasses, braces, and a skinny tie of his own. What drew them to They Might Be Giants? I asked. "They sing about Presidents and 'Planet of the Apes,'" Nathaniel explained. "It's not all about girls." "I think there should be a dork-rock tour of Weezer, They Might Be Giants, and Harvey Danger," Chris exclaimed, apropos of nothing in particular. "That'd be awesome! A whole crowd of people just like me!"

Despite fans like these, things weren't going in the Giants' favor that night: only about nine hundred people had bought tickets to a venue that holds twice that number, the police hassled the soundman about the decibel level, and someone kept flipping on the house lights. But eventually a few brave souls got up to dance; others joined in, and suddenly there was a dance party right in front of the stage. "Last night was a victory," Flansburgh pronounced the next morning at the Providence airport. "Here's to perseverance."

Their next gig, a free outdoor show in Nashville, was much more successful. Some fifteen thousand people watched the band pump out a strong performance on a barge tethered to the shore of the Cumberland River. Afterward Flansburgh did a meet-and-greet session with fans, off to the side of the stage, as he has done since the band started. He worked a long line--at least a hundred people--like a politician, tirelessly shaking hands, signing autographs, getting his picture taken with smiling fans, enthusiastically answering questions about the band. He stayed until he had met everybody--well over an hour. As the last people in line, a couple of twenty-something guys, strolled off into the night, Flansburgh called out, "See ya in the pit, fellas!"

The Giants will probably never play to audiences this size on a regular basis, but that's O.K. with them. Sales of "Mink Car" suffered because it happened to be released on September 11th, and shortly afterward their current label, Restless, drastically reorganized. But, in many ways, things have never been better for Flansburgh and Linnell: the theme song from "Malcolm in the Middle" won a Grammy this year; they are the subject of a full-length documentary called "Gigantic (A Tale of Two Johns)"; and on August 15th they'll be playing a twentieth-anniversary show at Central Park's SummerStage, a stone's throw from the spot where they made their debut. (This time, they won't have to carry their equipment over a stone wall.) "We lowered our expectations right away," Flansburgh says. "That's been very useful in having an enduring career in rock." He adds, "Is this a good enough life for us? I think the answer is pretty clear: yeah. We roll down the road with people cheering as the bus pulls away. There are a lot of harder things to do in the world."